One of my favorite design professors at the University of Washington would sometimes talk about the similarities of systems and spiderwebs. Touching one part of a web reverberates to every other part of it; the same is true of software products. Software is webs spun by hundreds or even thousands of people, sometimes according to a grand plan but most likely not. Systems are a game of

When we make even small changes to the features or overall structure of the web, those changes will ripple out and have unintended side effects. It is part of a design system team’s job to make those decisions, understand their impacts, and ensure that the people building the web know what’s going on.

This is why I think one of the more difficult parts of working on a design system team is making and communicating changes to the system. A few things can happen:

- Product teams object to the change, because it doesn’t work for their use case

- Breaking changes might require developers to re-factor their components

- The change causes visual or interaction bugs that need to be addressed, thereby increasing work for teams

- The full impact of a change isn’t clear until it’s already in production

Although design systems are in theory flexible and easily updated, the reality of software products today–especially those at larger companies that offer many products–means that making decisions that scale is often more challenging in practice.

[find real example - maybe strava]

Different areas of a product might use a mix of design system versions, and many areas won’t adhere to the system at all. When you make a change to the system, the divide between these areas can grow even larger.

Here are a few types of design system changes:

- Updating tokens, like colors and type

- Making updates to atoms/organisms/molecules, like adding variants or updating styling

- Deprecating old things

- Changing how things are named

Some types of changes require much more

I have a rough process that I follow for approaching most design system decisions:

Audit the surfaces

There is no better way to approach making a system-level decision than starting with a full accounting of the places your decision will impact.

Recently, I worked on a project to update the mobile type stack on Handshake’s iOS apps. I began by collecting Figma files of all of the recent mobile projects and brought them into an audit. I also collected screenshots from product areas I didn’t have a corresponding Figma file for.

Starting with a digital birds-eye view like this has a few main benefits:

- You can quickly test out how decisions scale to different scenarios

- It’s easier to spot inconsistencies between product areas

- Real examples are excellent fodder for justifying your decisions to product teams and leadership

Lean on the team

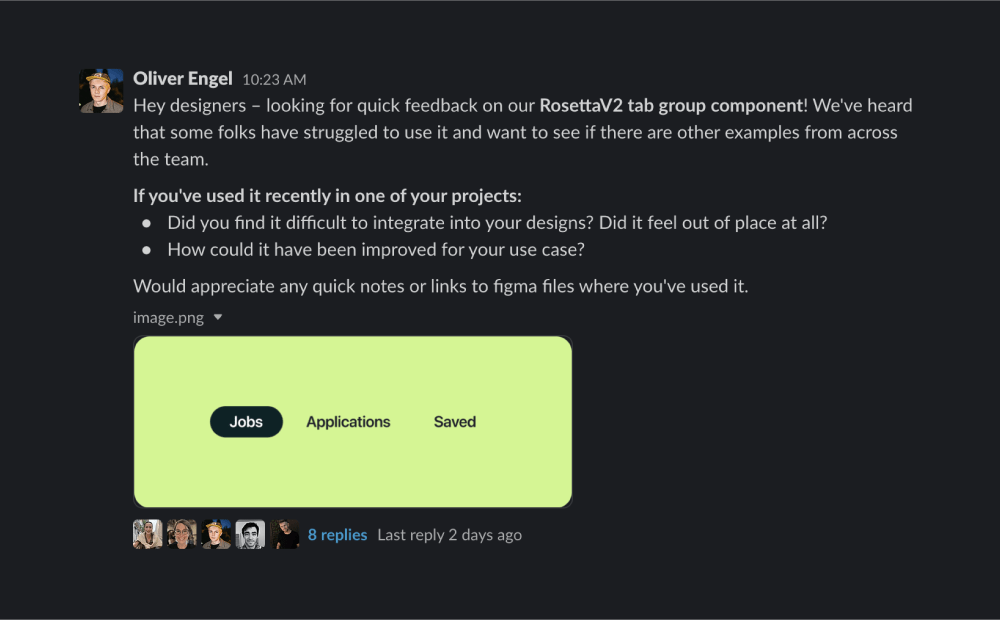

Don’t just rely on your own knowledge of the product to create your audit–you have a team full of product experts at your disposal. I like to make a public announcement that I’m looking into a certain area of the system, and ask the team to share their thoughts and relevant Figma links with me. I also like to give context on why I’m looking at the area and ask a couple pointed questions to get a conversation going.

Let the team know you’re looking into a certain component/style and get their early input

Let the team know you’re looking into a certain component/style and get their early input

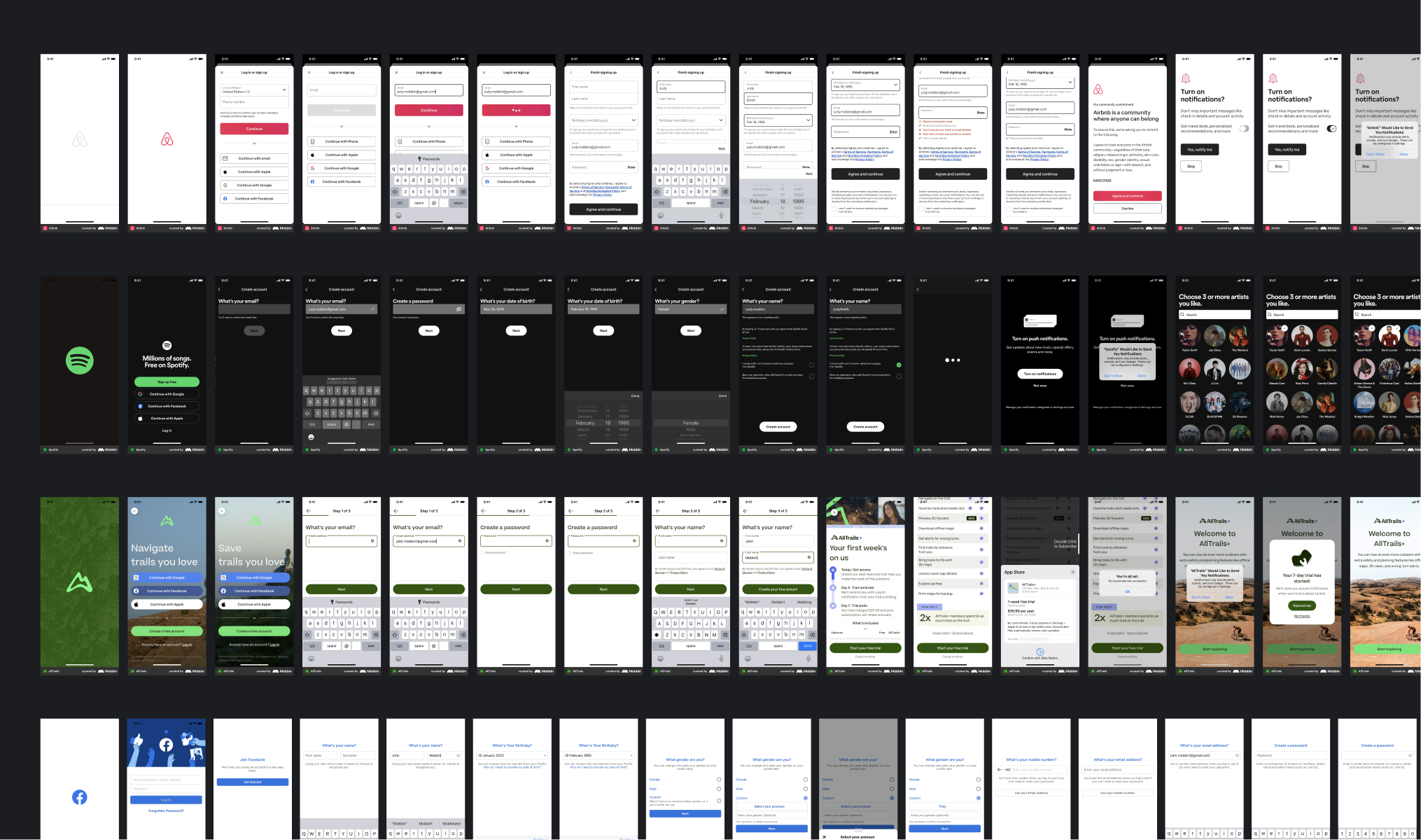

Reference other products

Auditing can also apply to examples from other software products. Very rarely do we as designers work on a pattern that hasn’t been successfully solved for in many ways. For example, it was particularly helpful for me to compare the common body sizes used by similar consumer apps to help inform what we should choose for our body style–looking at many examples can help you spot patterns to borrow.

Some of the consumer apps I referenced while making type changes to our mobile app

Some of the consumer apps I referenced while making type changes to our mobile app

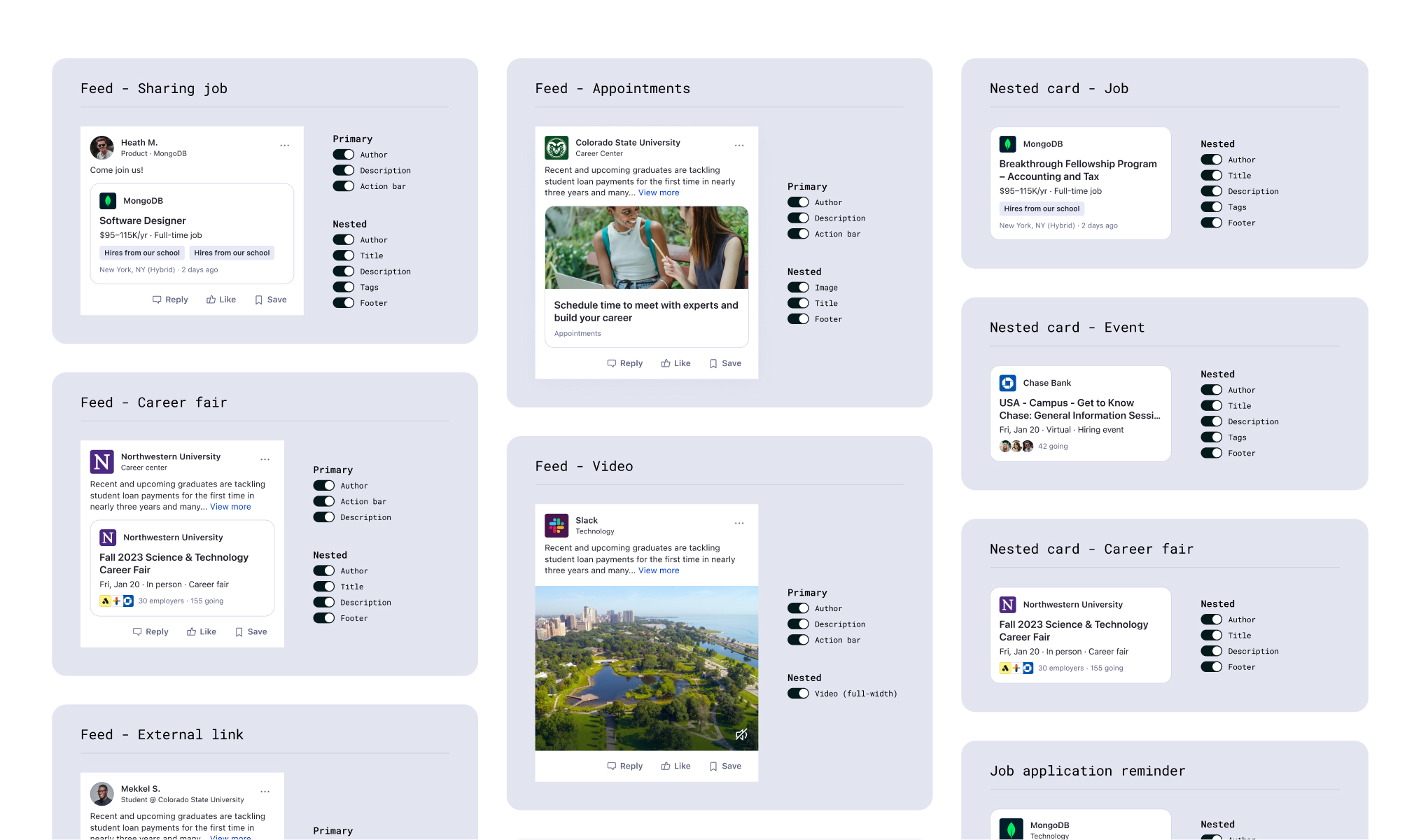

Play it out in a matrix

When considering a system-level change, there’s simply no substitute for playing out as many examples as possible to envision what the change will feel like. Assembling a matrix where you can see all the changes applied at a high level (and how those changes compare to the status quo) will help you identify edge cases, constraints, and other wonkiness that needs to be addressed.

Building out a matrix is a great next step after auditing the surface and will allow you to rapidly try a number of (big or small) changes and see how they feel.

Invite feedback early & often

Design systems teams should regularly jam with designers and engineers. It’s a good way to form ongoing relationships and get insight into how these folks are actually using your system. Staying in touch is particularly important when you’re proposing changes to the system: the changes you make will have real effects on your company’s product teams.

Feedback can be gathered in many forms, like:

- Regularly scheduled design system jams, where designers can get feedback on their work and get guidance on how to contribute back to the system

- Design systems designers joining team-specific jam sessions to get feedback on their proposed changes

- Asking the team for async feedback, like adding comments to your Figma file

Inviting feedback early & often is one of the most effective ways of bringing people along for the ride. It minimizes the chance you’ll get to launch day and get flooded with panicked, last-minute feedback.

Preview it in code

Designers place too much importance on our pixel-perfect Figma files. Figma has a way of distorting how products actually look and feel. The best way to counteract Figma tunnel vision is by working with developers to preview systems level changes live in code.

Here’s where it might work well for you:

- The change constitutes updates to global design tokens like text styles, spacing, border radii, or colors

- The changes do not require re-implementation of existing components

Both of the above scenarios are fairly simple requests of a developer; in both cases they are likely able to make the change in one place and preview how it looks across the product. This is not always practical or feasible for all types of systems decisions. Previewing breaking changes that require re-implementation of components across every instance where it lives could prove to be more costly and time-intensive than is worth it.

Some changes may even be possible to preview by playing with the CSS in your browser’s inspect mode. The closer you can get to the real product, the better you’ll be able to assess the impact of your changes.

Create documentation to stress-test your changes

I’m a firm believer that creating comprehensive documentation is the most helpful to the person authoring it, because it forces them to think systematically and catch things they might have otherwise missed, like edge cases, responsive behavior, and different contexts a pattern might show up in.

A snippet of documentation from a recent card system project I worked on.

A snippet of documentation from a recent card system project I worked on.

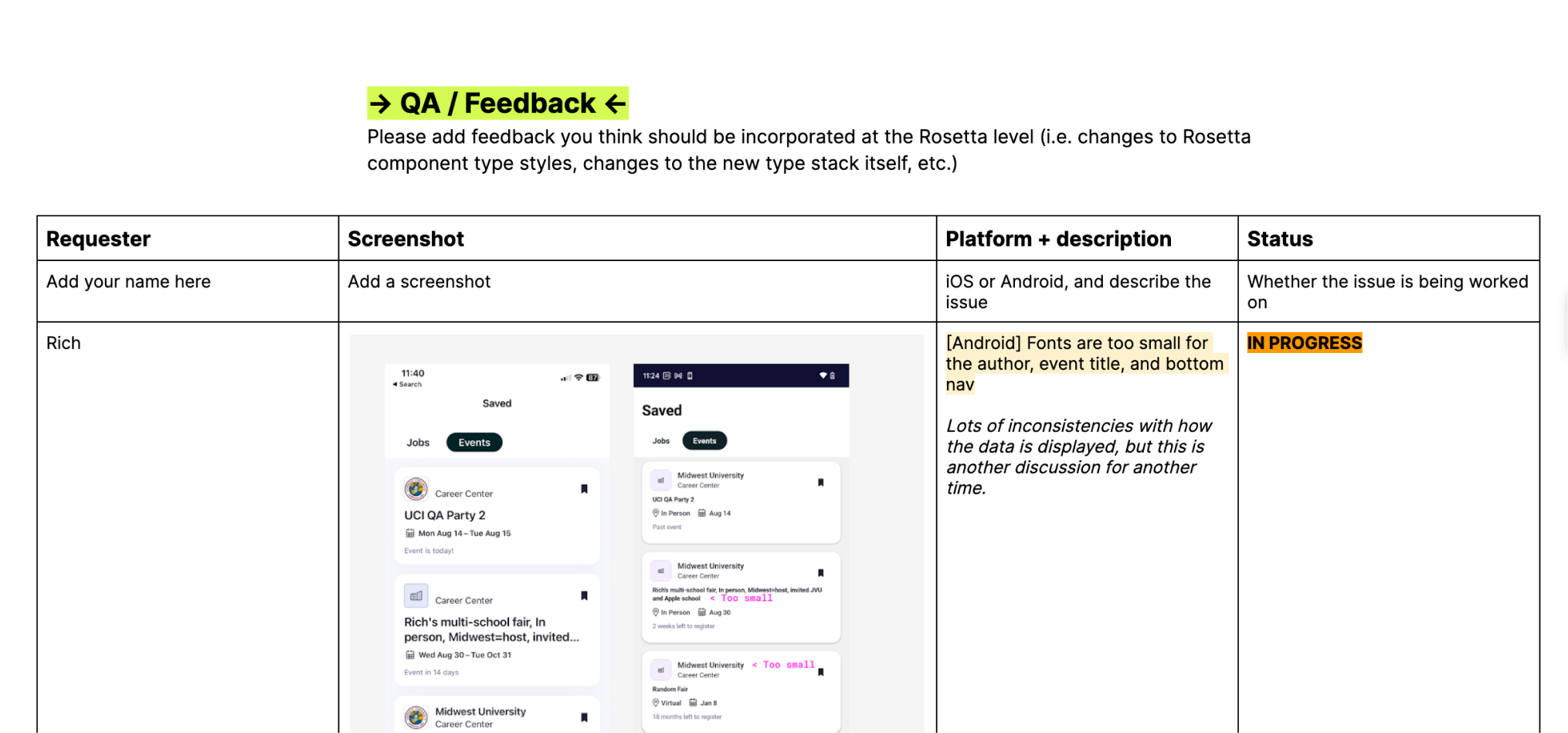

Solicit QA feedback on the real product in staging

Working with developers on enabling system changes in a staging environment lets you (and other product partners) play with the real thing. A great way to collect QA feedback is to a doc that describes the changes and has a template for people to input their feedback.

You may find that a full-on QA doc is unnecessary for small changes, where making tickets in JIRA (or another project management tool) works better. I like using a doc because not all feedback will end up as an actionable ticket, either because it is out of scope or does not need to be folded into the project.

When asking for QA feedback, create an easily-filled template for anyone to report an issue.

When asking for QA feedback, create an easily-filled template for anyone to report an issue.

Making decisions at the system level is scary. In a sufficiently large system, it’s nearly impossible to fully understand the impact even a small change might have in every corner of a product.

As a designer on Handshake’s design systems team, I’ve been learning how to address the inherent messiness of making system-level decisions.